Last October we wrote a short article arguing that the proposed 2024 Summit of the Future provides a unique opportunity to revisit the UN Charter. Just one month prior, the UN Secretary-General established the High-Level Advisory Board on Effective Multilateralism (HLAB) to “identify areas of common interest where governance improvements are most needed, to propose actions for how this could be achieved … and (to develop) a report to inform UN Member State deliberations ahead of the proposed Summit of the Future.” It was to members of the HLAB that the Global Governance Forum made a case during the 2022 General Assembly week in New York that the Summit could be used to announce a UN Charter Review conference as called for in Article 109 of the Charter. We were thus delighted to learn that their final report to the UNSG, issued last week and titled “A Breakthrough for People and Planet: Effective and Inclusive Global Governance for Today and the Future,” does state, without ambiguity: “The Summit of the Future is an opportunity to reaffirm our common commitment to the UN Charter and announce a Charter Review conference focused on Security Council reform” (p. 49).

This is a highly significant development. Virtually all of the major global catastrophic risks we face today are linked, in some form or other, to the inability of the human institutions that were created against the background of the chaos and destruction of World War II to adapt to the demands of a rapidly changing and increasingly complex world. To open the door to consideration of the many ways in which the UN Charter can be reexamined and realigned with the realities of the 21st century is an encouraging development and a unique opportunity to strengthen UN members’ commitment to renewed international cooperation.

Important priorities

In this and in subsequent articles, a group of us will briefly review some of the themes raised by the HLAB and how these issues can be leveraged to set in motion a process aimed at ensuring the Summit of the Future is able to live up to its potential as a pivotal conference in the history of the UN. In particular, we will discuss: Security Council reform, weapons and disarmament, climate change and the environmental crisis, gender equality, poverty and economic inequality, and global finance and related issues. We believe responding to these areas of concern is essential to ensuring a more effective multilateralism and represents opportunities where tangible action can catalyze transformative change. In this initial article we take up two important topics raised in the HLAB report: poverty and inequality, and global finance.

Poverty and inequality

One of the most exciting developments in the constellation of recent proposals is related to developing indicators that move measurement beyond GDP. This initiative is something with which the Global Governance Forum is very much aligned and looks forward to engaging. However, it is the case that a reasonable proxy for wellbeing remains indicators of material wealth—especially when it comes to those living in poverty and, even more so, extreme poverty. As such, recognizing the shortcomings of such a lens, it is still vitally important that we assess progress (or not) along this continuum.

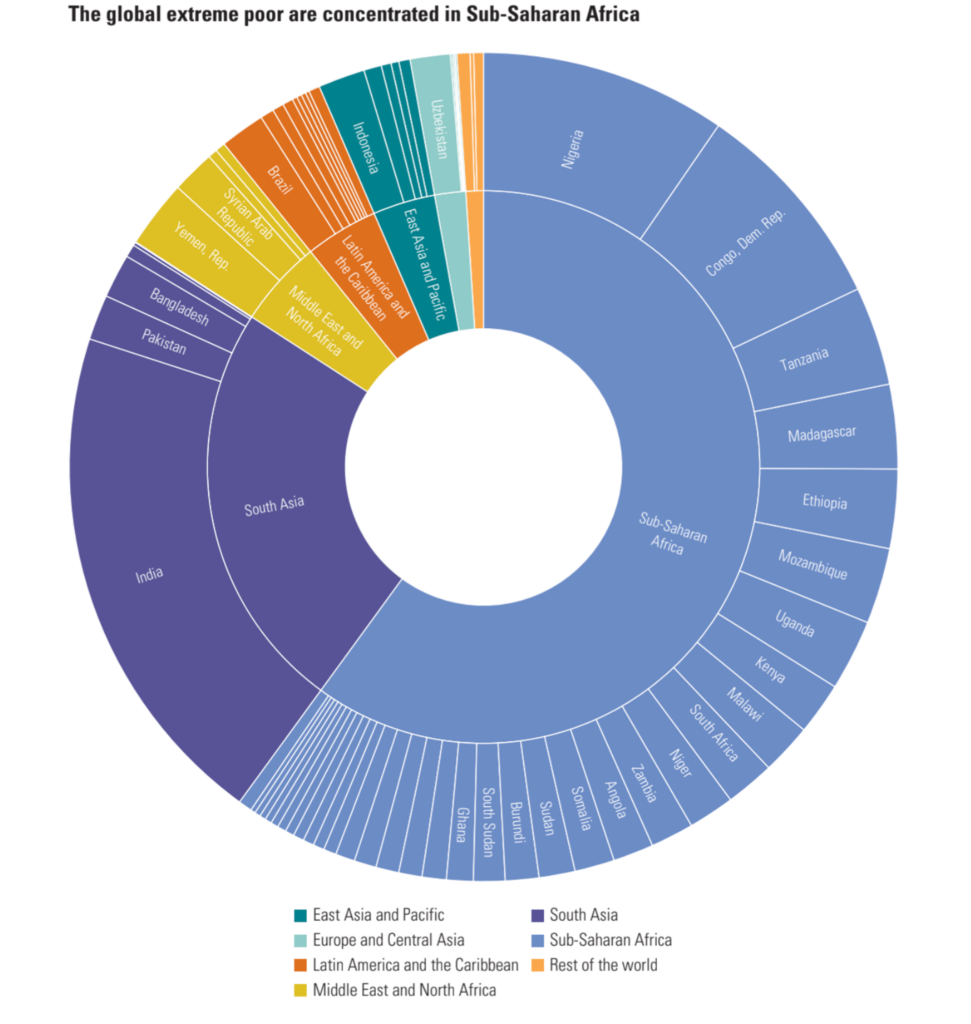

One narrative that is often put forward by development economists is that great progress has been made in recent decades in reducing the incidence of extreme poverty. Using the World Bank’s poverty line of $2.15 income per day, the number of people in extreme poverty has been reduced from close to 2 billion in 1990 to something on the order of 700 million people in 2022. However, this data requires two important qualifications. The first is that much of this reduction is accounted for by high economic growth rates in China and, to a lesser extent, India. Considerably less progress has been made in Sub-Saharan Africa, which remains the largest pocket of extreme poverty in the world.

The second is that the extreme poverty line used by the World Bank is exceptionally austere, with people in this group characterized by a very precarious existence, high incidence of malnutrition, illiteracy, lack of access to basic infrastructure such as running water and electricity, to say nothing of other social protections, such as health care. Indeed, it is not at all an exaggeration to characterize this level of poverty as being degrading and demoralizing for those affected. Using a poverty line of $6.85 income per day—which some economists suggest still leaves people struggling to make ends meet—a full 47 percent of the world’s population is poor today. Moreover, the depths of inequality – both within countries and between them – has, by and large and contrary to SDG 10, accelerated since 2015. Widespread poverty and lack of access to nutrition and basic services and widening income disparities are not only detrimental to the well-being of a large segment of the world’s population, but they are also a threat to the security and stability of the world.

There is a moral case for better social protection, even if this means a fundamental rethinking of the structure of national budgets. We live in a world in which a completely accidental event—the country of our birth—plays a fundamental role in the prospects we face as human beings. If we are born in a country with adequate social protections, such as Norway to take but one example, we will have enormous opportunities to develop our inherent capabilities. For in Norway, it is highly probable not only that we will safely reach the age of 5, be well fed and educated, and have access to modern medical and health facilities; but we will also be provided for in our old age, since in Norway, economic policies have incorporated the concept of sustainability in their design, including in the management of public finances and the responsibilities of the state to future generations.

By contrast, there may be some contexts where, by virtue of our birthplace, we may not survive to the age of 5; and if we do, we are more likely to become part of the 800 million people in the world who suffer from malnutrition, or whose talents may be stunted not only by the lack of good nutrition during the early stages of the development of our brains, but by the absence of quality education. And, of course, on average, we may live to the age of 59, rather than the 79–80 years seen in other parts of the world. This is a profoundly unfair reality; there is no ethical framework in which this situation could be characterized as consistent with elemental notions of justice. And, in this sense, one would be well justified in suggesting that such gross inequalities of opportunity demonstrate that no country can yet be considered fully developed as a holistic notion of development implicates all countries when such injustice prevails.

Strengthening the underpinnings of our systems of social protection—whether through the gradual introduction of something like a universal basic income, universal social protection, or by other schemes which clearly demonstrate that their merits outweigh their costs—would go a long way to help erase poverty, malnutrition, illiteracy, and gender discrimination at a time when the global economy´s productive capacity is at an all-time high, suggesting that poverty eradication and related problems reflect less the absence of resources than inefficient allocation of resources and lack of global solidarity.

Emerging from COVID-19 and moving forward with the likelihood of future pandemics, it is, in fact, the socially optimal path, affording greater protection everywhere. This may well be one of the more enduring lessons from the calamities of COVID-19. The United Nations, the ILO, and the SDGs all, to varying degrees, speak about the merits of such an approach. It is well known that these investments more than pay for themselves in the long run, which demonstrates that the matter is not simply one of rebalancing budgets.

There are many factors – political fracturing, social distrust, military aggression – which stand between good policies and their implementation. These barriers, factors which contribute to the lack of political will, must be overcome through the creation of enabling environments. What is the most effective system to ensure that economic justice through the reduction of inter and intra country inequality can be realized? How can those with greater wealth – whether individuals, corporations, or nations – be encouraged to see in its redistribution the wellbeing of all the human family? We should naturally turn to the global financial architecture to encourage the realization of such a global economic ethic.

Global finance

Just as was mentioned to open the previous section, a caveat is in order – and one also articulated by the HLAB. As stated in their report, “[t]o be effective in the face of twenty-first century challenges, the World Bank and the other Multilateral Development Banks must update and expand their mandates to include the financing of global public goods and the protection of the global commons, alongside the twin goals of poverty alleviation and shared prosperity.” That does not, of course, absolve them nor the international community of their duty to work towards the eradication of poverty, but it is important to recognize the value of an expanded scope given the needs of humanity today.

Another key issue raised in the HLAB report concerns the so-called Global Financial Safety Net and the extent to which its various components—IMF resources, regional financial arrangements, and bilateral swap arrangements—provide adequate “firepower” at a time when various crises are likely to have spillover effects given the systemic nature of many of the risks we face.

By way of example, at the time of the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015 it was estimated that over the next 15 years, the world would need to spend some US$75-90 trillion on clean infrastructure. The scale of these investments was expected to put pressure on public sector finances and therefore most scenarios envisaged a significant role for private sources of funding. Covid-19 only heightened the importance of the role of private capital in financing the transition to low-carbon resilient (LCR) infrastructures given that, according to the IMF, the fiscal impact of the pandemic during 2020 amounted to an increase of close to 20 percentage points of GDP in public debt levels worldwide on average. It is also necessary to address the continued presence of sizable fossil fuel subsidies, which contribute to accelerate climate change and worsen income inequality.

Given these obstacles, it is expected that public concessional finance would continue to play a role in de-risking LCR infrastructure projects. At the moment, instruments such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) together with the multilateral development banks have been the primary vehicles to deliver climate change finance. However, such pledges, even if fulfilled, are woefully insufficient to provide the resources needed to ensure compliance with the temperature ceiling commitments made in the Paris Agreement. The above discussion raises the question of whether there is a role for the IMF in being part of the solution to the above funding shortfalls or whether that role should be played primarily by the multilateral development banks and well-regulated private capital.

In this respect, we find it most relevant that the HLAB report calls for ensuring “greater automaticity and fairness in SDR allocations.” Special Drawing Rights (SDRs, a form of unconditional liquidity created by the IMF) came into being in 1969 as an attempt to bolster countries’ official reserves. There were three SDR issues between 1969 and 2020, by far the largest of which took place in 2009 (equivalent to US$250 billion), as a response to the financing needs of the global financial crisis. In August 2021 the Board of Governors of the IMF approved an SDR allocation equivalent to US$650 billion, to “boost global liquidity.” While indicating that US$275 billion of this allocation would be made to emerging economies and developing countries, the IMF suggested that it would continue to give attention to the question of how to deploy this windfall for the benefit of developing countries. The starting point of this debate was that lower-income countries had been profoundly impacted by COVID-19 and had had difficulties in confronting the challenges of vulnerable health systems, limited fiscal space and, in many of these countries, unsustainable debt burdens.

The Fund’s shareholders seemed to support a narrative that substantial financial support over the next several years in pandemic funding and other spending in the case of low-income countries might make it possible for these countries to get back onto a more sustainable growth path. In this respect, the 2021 SDR allocation was an important innovation, suggesting a new role for the Fund in times of systemic crises through utilizing SDRs.

Beyond the immediate issue of the uses to be made of such SDR allocations, more generally, there would appear to be an urgent need to overhaul and simplify the system under which the Fund may issue SDRs under exceptional circumstances, such as times of crises. At present the system is unduly ponderous. The size, integration, and complexity of financial markets today dwarfs what we had in the 1980s and the costs of an unresolved systemic crisis today are, likewise, extremely high. In any case, reforms in this area should also introduce protections to limit moral hazard and help to build trust. The idea is to put in place well-funded crisis financing mechanisms available to all IMF members, as an alternative to precautionary reserve accumulation, which is what countries have done in recent decades in a big way as a form of self-insurance. As part of its efforts to improve global liquidity management, the IMF should be allowed to mobilize additional resources by doing the following: tapping capital markets and issuing bonds dominated in SDRs (something that would not require amending its Articles), making emergency SDR allocations under considerably more stream-lined procedures, and allocating SDRs regularly to supplement country’s reserve positions. The issues of improving governance in the international financial institutions and revamping existing nearly broken mechanisms for debt relief will be addressed in a subsequent article.

Conclusion

The aforementioned considerations, largely inspired by the HLAB report, are offered as part of the conversation leading up to the Summit of the Future. Ultimately, what both sections above center around is finding approaches and institutions which can bring to reality the expressions of global solidarity increasingly articulated the world over. Expanding our notions of economic justice to ensure that the lottery of birth is less determinative of our ultimate contribution to the human tapestry; finding new and creative mechanisms by which to allow low-income countries to implement the kinds of policies we know will redound to the benefit of their citizens – and, in turn, the world; reducing inequality at national and global levels; and moving beyond the notion of GDP and income as the defining indicators of progress rather than as the proxies they truly are. If the Summit of the Future is to be a success in the fields of poverty eradication and the global financial architecture, it will move beyond the constrictions of our historical notions and allow us to find new and creative solutions to 21st century challenges.

WRITTEN BY AUGUSTO LOPEZ-CLAROS AND DANIEL PERELL